Submitted by Arn Pearson on

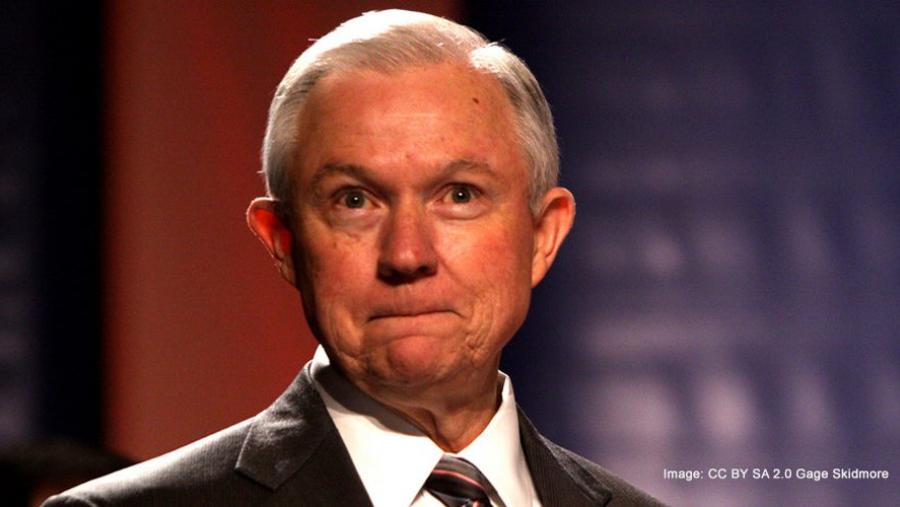

The most heated exchanges during Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ appearance before the Senate Judiciary Committee last week concerned his ever-shifting explanation of what he discussed—or didn’t discuss—with Russian officials while serving as Donald Trump’s “go-to person” on foreign policy during the 2016 presidential campaign.

The only thing shrinking faster than Sessions’ initial denial of those communications is his credibility.

When asked during his January confirmation hearing if he had had any communications or contact with the Russians, Sessions responded “no.” He also failed to disclose any such meetings when he applied for a security clearance.

The record is now clear, however, that Sessions spoke with Russian ambassador Sergey Kislyak on at least three occasions in 2016—in April, at the Mayflower Hotel after Trump gave his first major foreign policy speech; in July, at the Republican National Convention, after Sessions nominated Trump to be the GOP’s candidate; and in September, at his Senate office, just as the story of Russia hacking the Democratic Party was blowing up.

When the Washington Post first broke the story on March 1 about two of those Kislyak meetings, Sessions quickly qualified his denials. On Twitter and again at his press conference on March 2, Sessions said, “I never had meetings with Russian operatives or Russian intermediaries about the Trump campaign.”

As Sir Walter Scott eloquently wrote, “O, what a tangled web we weave when first we practise to deceive.”

Pressed on that point at a June Senate Intelligence Committee hearing, Sessions said—26 times—that he could not “recall” what was discussed in his Kislyak meetings.

Unfortunately for Sessions, Kislyak could.

In July, the Washington Post disclosed an intelligence leak that Kislyak’s communications with his superiors had been intercepted, and that Kislyak reported that he and Sessions had “‘substantive’ discussions on matters including Trump’s positions on Russia-related issues and prospects for U.S.-Russian relations in a Trump administration.”

Caught with his metaphorical pants down, Sessions is now hiding behind an even smaller fig leaf.

Pressed on the point by Senators Leahy and Franken at last week’s hearing, Sessions said, “I have never had a meeting with any Russian officials to discuss any kind of coordinating campaign efforts.” He added, “I conducted no improper discussions with Russians at any time.”

Meanwhile, Sessions’ memory seems to have returned—at least in part—about his campaign policy conversations with Kislyak. Under pressure from Senator Leahy, Sessions testified at the October 18 hearing that,

“I don’t think there was any discussion of—about the details of the campaign, other than—it could’ve been that, in that meeting in my office, or at the convention—that some comment was made about what Trump’s positions were. I think that’s possible.”

When Leahy quizzed Sessions about his post-election communications with the Russians, Sessions flatly denied discussing Russian interference in the elections, but said he could not recall if emails were discussed, and limited his denial of discussing sanctions with the Russians to the Magnitsky Act.

Sessions’ claim that he did not discuss policy matters with Kislyak during the campaign is just not credible, both in light of the intercepted Kislyak communications and the fact that everyone else around Sessions did.

Sessions served as Trump’s lead foreign policy advisor and chair of his National Security Advisory Council during the campaign and, with the help of his Senate chief of staff, Rick Dearborn (now a deputy chief of staff at the White House), set up a campaign policy shop in Alexandria, Virginia in April 2016. As part of that operation, Sessions met frequently with Dimitri Simes, a Russia expert educated in Moscow; Richard Burt, a lobbyist with Russian clients; J.D. Gordon, a former Pentagon spokesperson; and Carter Page, an oil industry consultant with strong Russia ties.

All four of those men advocated softening the United States’ sanctions against Russia imposed after Russia’s annexation of Crimea. And Gordon and Page orchestrated a change in the GOP’s platform—the only platform fight the Trump campaign engaged on—to weaken its position on Russian aggression in Ukraine.

Indeed, when Sessions met with Kislyak the day the RNC adopted its platform, he was accompanied by Gordon and Page. According to Sessions’ new Senate Judiciary Committee testimony, that was also the day Kislyak asked for a meeting at Sessions’ office.

Gordon also spoke separately with Kislyak at the RNC “about Mr. Trump’s desire to reset the strategic relationship,” and told the press that Page and Kislyak met at length about improving U.S.-Russia relations on issues of energy security and counterterrorism.

In this context, Sessions’ claim that he met with Kislyak in his capacity as a senator, not Trump’s chief policy advisor, and did not discuss campaign positions just doesn’t hold water.

“I met with 26 ambassadors in the last year, and he was one of them,” Sessions argued under questioning last week by Senator Leahy.

But Sessions had precisely zero meetings with foreign ambassadors in 2016 before joining the Trump campaign in March. All of the meetings—including those with ambassadors from Russia, Ukraine, and seven other Eastern European countries—occurred while he served as Trump’s highest ranking political ally and advisor.

During that same period, Sessions conspicuously abandoned his position as a well-known hawk on Russia’s threat to the U.S. and European security. “I think an argument can be made that there is no reason for the U.S. and Russia to be at this loggerheads,” Sessions said shortly after joining the Trump campaign.

Clearly Sessions is on the defense, and trying very hard to hide behind a straw-man argument about coordination to distract attention from his previous lies about the existence and nature of his meetings with Kislyak.

The Senate—and special counsel Robert Mueller—should not let him get away with it.

This article was written by Arn Pearson in his capacity as a senior fellow for People for the American Way and first published on that group’s website.