Submitted by Anne Landman on

"We do not want children to smoke," British American Tobacco (BAT) declares on its website. But the company that describes itself as the "world's most international tobacco group" routinely violates its own voluntary international marketing and advertising standards, according to a July 1, 2008 BBC-TV This World investigation. BAT was caught in Malawi, Mauritius and Nigeria using marketing tactics that are well-known to appeal to youth: advertising and selling single cigarettes, and sponsoring non-age-restricted, product-branded musical entertainment. (See also "Playing with Children's Lives: Big Tobacco in Malawi.")

"We do not want children to smoke," British American Tobacco (BAT) declares on its website. But the company that describes itself as the "world's most international tobacco group" routinely violates its own voluntary international marketing and advertising standards, according to a July 1, 2008 BBC-TV This World investigation. BAT was caught in Malawi, Mauritius and Nigeria using marketing tactics that are well-known to appeal to youth: advertising and selling single cigarettes, and sponsoring non-age-restricted, product-branded musical entertainment. (See also "Playing with Children's Lives: Big Tobacco in Malawi.")

When a company adopts and prominently touts its voluntary behavior codes, only to end up violating them, people start asking questions: What are the real reasons for these codes? Are they just for public relations (PR) purposes? To, as they say, 'cover your a*s' (CYA)? How did they arise? What, if any, value do they have?

PR or not PR?

Industry representatives offer mixed responses to the question of whether or not voluntary codes are driven by a PR agenda.

Lynne Omlie, staff liaison for the Code Review Board of the Distilled Spirits Council of the United States (DISCUS), backed up by general counsel Frank Coleman, insisted that public relations played no part in the liquor industry's voluntary codes.

The Beer Institute was inadvertently less ingenuous about the public relations role of its codes. It immediately referred an inquiry on its voluntary policies to the Washington, D.C.-based public relations firm, Chlopak, Leonard, Schechter and Associates (CLS), which specializes in "high-stakes challenges in adversarial or competitive environments." Both CLS and the Institute ducked questions about the relationship between corporate codes and PR. The Institute emailed a statement from its president, Jeff Becker: "Brewers and beer importers execute their advertising and marketing campaigns in a responsible manner directed to adult consumers." It noted the Federal Trade Commission's June 2008 report which "highlights brewers' conscientious compliance with the Beer Institute Advertising and Marketing Code" and "reaffirms that self-regulation continues to work well."

But whether or not their codes are designed to improve image, both the alcohol and tobacco industries recognize that the exposure of practices that violate their codes can lead to public relations problems. The alcohol and tobacco industries are especially aware of the charge that they seduce minors, both to develop brand loyalty and to boost sales. In addition the impact on profits, bad PR around code violations can spur governments to issue tighter regulations.

Omlie insisted that the hard liquor industry DISCUS represents does not aim its ads at minors and pointed to beer advertising as the culprit.

Despite beer/malt liquor industry codes that proscribe marketing to minors, spokesthings such as Bud frogs and lizards, Spuds MacKenzie and Whassup space-alien dogs appeal to teens, as do such familiar, sweet-tasting "alcopop" products such as Rick's Spiked Lemonade, Hooper's Hooch and Skyy Blue.

More! New! Exciting! Problems With Voluntary Codes

As effectively as voluntary codes have worked to preserve corporate credibility, power and political control, the downside for the public is that these codes can actually burden civil society in many ways:

1) Enforcement is Reactive, not Proactive As was the case for the distilled spirits industry, voluntary codes are usually enforced only through complaints and typically provide for little or no proactive enforcement. Violations can continue until the misbehavior is discovered and reported by the rare whistle blower, someone outside the company, or a rival company seeking a competitive advantage. Thus it often falls on the public to assume the burden of observing and evaluating corporate behavior or advertising, and reporting violations.

Few ordinary citizens, though, have the time or knowledge to monitor advertising and behavior for compliance with corporate codes, especially in less developed countries such as Malawi, Mauritius and Nigeria, where BAT violated its own codes.

While DISCUS publishes a semi-annual report on violations of the liquor industry's advertising code, most companies are under no obligation to reveal data to the public about the number of complaints they receive, the locations and products involved, or other information. If fines are attached to breaches of the code, they are rarely commensurate with the profits derived from the breaches. For example, according to a 1999 Philip Morris USA Chairman's Briefing Book (approved by the company's legal department) [see pages 7822-7823], PM merely suspends a retailer's access to special cigarette sales promotions for one to four months, for the first, second, third and fourth violations respectively, of laws prohibiting cigarette sales to minors.

2) Companies Can Maintain Secrecy Unlike a public regulator who launches legal proceedings -- individuals and groups rarely have any power to force companies to release potentially incriminating documents. The biggest exception to that impotence -- the effectiveness of lawsuits in gaining internal documents during discovery -- helps explain corporate enthusiasm for "tort reform."

3) Corporate Codes are Limited in Scope Corporate codes address only those issues an industry wants to deal with publicly. Typical codes focus only on high profile issues that companies regard as potentially threatening. The codes typically ignore larger and more complicated problems, such as those caused by "downstream" entities such as suppliers, sub-contractors and distributors.

4) "Corporate Code" Strategy Has Spread to Other Industries The tobacco industry's success in using voluntary codes to its advantage has demonstrated the value of the strategy to the larger globalized corporate world. As a result, similar voluntary codes have been adopted by other industries including the beer industry, pharmaceuticals, the cellular phone industry, the forest products industry, and gambling, to name but a few.

A Model Voluntary Code Enforcement Scheme?

DISCUS claims to have one of the most comprehensive voluntary codes and organized enforcement schemes in the United States. "Throughout the decades, there has been 100 percent compliance among DISCUS members and overwhelming compliance by non-DISCUS members with Code Review Board decisions," Omlie wrote in an email.

DISCUS claims to have one of the most comprehensive voluntary codes and organized enforcement schemes in the United States. "Throughout the decades, there has been 100 percent compliance among DISCUS members and overwhelming compliance by non-DISCUS members with Code Review Board decisions," Omlie wrote in an email.

DISCUS' voluntary advertising code covers all forms of liquor advertising, including print, the Internet, TV, packaging, labels and promotional materials. Among the bad practices it attempts to curb is gratuitous sexuality in advertising to media where 30 percent of the audience is under 21.

DISCUS' enforcement scheme utilizes a Code Review Board made up of "no fewer than five members in good standing" of DISCUS' Board of Directors. Thus all of its review board members are liquor industry insiders.

DISCUS' code enforcement works as follows: 1) a company runs an ad that violates the code; 2) someone reports the violation; 3) DISCUS' Code Review Board reviews the ad and the offending company is informed of the complaint; 4) the Board rules on whether or not the ad violates the code; 5) if it violates the code, the board informs the company and gives it a chance to change or pull the ad. On rare occasions where Review Board members reach a tie about whether an ad violates the code, DISCUS consults a three-member, outside advisory board that can give "confidential, nonbinding" recommendations as to the disposition of an ad.

DISCUS publishes the results of its Code Review Board hearings in a semi-annual report, which DISCUS points to as evidence that it is adequately policing itself.

If, in spite of repeated notices, a recalcitrant company keeps violating DISCUS' code, DISCUS writes it up repeatedly in its semi-annual reports. That's it. There are no limits specified in the code about the number of violations a company can have, and there are no financial incentives not to violate the code, such as penalties or fines. There appear to be no sanctions against offenders beyond the "naming-and-shaming" scheme of the Code Review Board's semi-annual reports. If a company doesn't care whether it is featured repeatedly in DISCUS' semi-annual reports, it appears that it can advertise its products however it likes for as long as it wants.

What "100% Compliance" Really Means

DISCUS boasts that it gets "100 percent compliance" with its code from its member companies. That absolute number does not mean a total absence of advertising code violations by liquor companies, however. Rather, it means that every company that was caught, reported and confronted, agreed to change or pull its offensive ads. Companies that run offensive ads but don't get caught are considered, statistically, as though they were compliant with the code.

An ad by Chambord was deemed unconforming to the DISCUS code in DISCUS' 2004 Code Review Report. Chambord was a non-member of DISCUS at the time. The advertiser failed to respond and DISCUS took no further action.

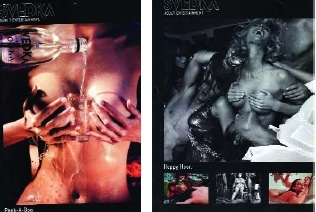

A further example is a non-complying Sveda Vodka ad run by a non-member of DISCUS (at left), featured in DISCUS' Jan-June 2005 Code Review Report. DISCUS informed the company that the ad was out of compliance with Responsible Content Provisions Nos. 25, 22 and 21 of the Code, "due to the sexually graphic images and gratuitous nudity depicted in these materials, as well as the demeaning images of women." Despite DISCUS urging the advertiser to revise the ad, the report states, "Action by Advertiser: No response from the advertiser. Status: Board continues to urge the advertiser to revise these advertising and marketing."

A further example is a non-complying Sveda Vodka ad run by a non-member of DISCUS (at left), featured in DISCUS' Jan-June 2005 Code Review Report. DISCUS informed the company that the ad was out of compliance with Responsible Content Provisions Nos. 25, 22 and 21 of the Code, "due to the sexually graphic images and gratuitous nudity depicted in these materials, as well as the demeaning images of women." Despite DISCUS urging the advertiser to revise the ad, the report states, "Action by Advertiser: No response from the advertiser. Status: Board continues to urge the advertiser to revise these advertising and marketing."

The Spin Cycle Begins

Voluntary corporate codes were born out of corporate misbehavior that resulted in public relations disasters. In the early 1970s, the public learned that the American transnational conglomerate, International Telephone and Telegraph (ITT), had played a significant and hidden role in overthrowing a democratically-elected government, the new government of Chile's Salvador Allende.

In 1970, the year Salvador Allende became president of Chile, ITT owned 70 percent of the Chilean Telephone Company, Chitelco. ITT's $200 million investment was by far the largest holding of any single U.S. corporation in Chile. The election of the Marxist, Allende, and a growing socialist movement in Chile had aroused corporate concerns that the country would nationalize the phone company and other important businesses and services. The Nixon administration was also worried about a leftist regime coming to power in Chile. These mutual concerns led to behind-the-scenes meetings between ITT executives and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) officials. ITT secretly contributed $1 million to a clandestine U.S. effort to short-circuit Allende's campaign for the presidency. That effort failed, and some of the corporate fears were realized when Allende did indeed nationalize important Chilean assets.

On September 11, 1973, a CIA-backed military coup assassinated Allende and installed Augusto Pinochet. During his 16-year rule, the right-wing, U.S.-supported dictator imprisoned, tortured and killed thousands of Chileans.

When word of ITT's involvement in Chile leaked out in 1973, public outrage grew, the U.S. Congress launched an investigation into ITT's involvement, and called company executives to testify. In 1979, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) officially charged ITT officials with lying to Congress about their involvement in Chilean affairs.

Although the DOJ later dropped the charges, claiming that prosecuting the case would involve revealing U.S. national secrets, the public relations damage was done. The spotlight that fell on ITT's behind-the-scenes activities reflected on the secret activities of other multinational companies. Public pressure increased, clamoring for more control over runaway corporate power. Powerful corporations, fearing external oversight, responded by enacting voluntary codes of conduct as a way to assure an upset public that they would keep their behavior within acceptable limits, and police themselves.

Rinse and Repeat

Cigarette companies were among the first to understand the value of voluntary behavior codes in staving off more serious government regulation of their activities. In the beginning, industry confined limitations on its conduct to internal agreements, not released to the public.

Around the time of the ITT-Chile debacle, Philip Morris and other American tobacco companies quietly set-up a private, voluntary agreement: They would list the amounts of tar and nicotine in their products in advertisements, but not on cigarette packages. This strategy helped cigarette companies evade advertising restrictions, and curb Federal Trade Commission threats to interfere in their commerce. This success demonstrated to cigarette makers and other industries how voluntary conduct codes could serve their corporate interests.

Clearing the Smoke

A good place to start discovering how industry uses voluntary codes is the extensive paper trail provided by internal tobacco industry documents. The 1998 Master Settlement Agreement between U.S. states and cigarette companies required the companies to make public millions of previously secret documents. The records, now available at the Legacy Tobacco Documents Library, have ironically turned the tobacco industry into a highly transparent portal for exploring the real intent behind voluntary codes.

Revelations include:

1) A 1989 Tobacco Institute report, Tobacco Advertising Restrictions Working Group Strategy Report, demonstrates how voluntary codes help industry defend itself against charges that it is doing something wrong and provide "ammunition" to pro-industry allies, while providing a way for industry to spin itself positively and project good faith to the public.

2) A 1991 Philip Morris Corporate Affairs Europe (PM) plan proposed a voluntary code of conduct to help avoid regulation: "A first step [to fighting proposed advertising restrictions in Poland] was a meeting between PM management and the [Polish] Minister of Agriculture, after which the latter became an active supporter of a voluntary code of conduct as a viable alternative to stringent restrictions ... " [Emphasis added.]

3) An undated, eight-page strategy document from BAT states the company's intent to enact a voluntary code of conduct to "demonstrate [company] responsibility" to policymakers and "enable government to claim that they 'have done something' to address a negative corporate behavior ... which is what they [legislators] need in answer to pressure groups." Thus voluntary codes gave cover to legislators, by providing them with something to point to, to assure the public that they have acted to deal with offensive corporate behavior.

4) An urgent November 1995 fax from BAT Kenya discusses an impending tobacco control bill: "The issue of sports sponsorship is mentioned [in the bill] and seems to actually amount to a total ban of sports sponsorship in Kenya. We need to resist this using the time honoured method of a voluntary code."

5) A 1992 interoffice memo from PM Europe about introducing a voluntary code in Greece says the code "is being put in a drawer for a rainy day" -- meaning it will be pulled out when needed to avoid regulations.

How Companies and Industries Use Voluntary Codes

But the public -- exposed to a litany of revelations about corporate complicity in sweatshop conditions, child labor, pollution, fraud, union-busting and agricultural practices -- was growing increasingly skeptical of businesses and the voluntary codes they adopted.

"As awareness of the dangers of transnational corporations increases, the use of these codes increases," explained Patti Lynn, campaigns director at Corporate Accountability International. "The public concern is for policy initiatives, because these codes defer policy. And when voluntary codes get matched up with more credible institutions, they become more dangerous [by providing better cover]" she said, citing the mother of all codes, the United Nations Global Compact.

In 2007, the United Nations initiated its Global Compact nominally to curb harmful policies and behaviors by transnational corporations that lead to corruption and violations of human, labor and environmental rights. The Compact urges corporations to take a precautionary approach to environmental challenges, to avoid complicity in human rights abuses, to recognize workers' right to collective bargaining, and to eliminate forced and child labor, among other tenets.

Corporate watchdog organizations (including CorpWatch) have criticized the U.N. Compact because it lacks teeth: "It's not enforceable; it has no enforcement mechanism," Lynn said. The U.N.'s own description of the Global Compact on its Web site, says the Compact "is not a regulatory instrument -- it does not police, enforce, or monitor companies' behavior. Instead, the Compact relies on companies' public accountability, transparency, 'enlightened self-interest,' and on civil society to assure compliance with Compact principles." The Compact, Lynn says, "allows transnational companies to increase their credibility by wrapping themselves in the U.N. flag."

Despite having signed on to the Compact, companies continue to violate its tenets. As CorpWatch previously reported, Aventis violated Principle No. 7, "support a precautionary approach to environmental challenges," by introducing genetically engineered StarLink corn in the U.S. Nike violated Principle Number 3 in Vietnam, China, Indonesia, Cambodia and Mexico by failing to protect the "freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining."

Voluntary codes have also helped keep tobacco companies and other ethically suspect industries from becoming marginalized in the world of public commerce -- despite decades of conspiratorial and fraudulent conduct. Staying in the mainstream is vital to their survival; the more an industry is perceived as mainstream (as opposed to rogue), the more credibility it commands where it really counts, with lawmakers and regulators. Maintaining credibility and a patina of mainstream respectability increases the chances that an industry will be given a seat at the table in any regulatory discussions, and thus get a shot at weakening strictures against it.

So What Can Be Done About Voluntary Conduct Codes?

There are other models besides the DISCUS advertising code and the Global Compact that provide better protection to the public, workers, and the environment. One conduct code with potential for adequate enforcement is the World Health Organization's groundbreaking Framework Convention for Tobacco Control (FCTC), now known as the Global Tobacco Treaty (GTT), implemented on February 27, 2005. Under the GTT, countries that are parties to the treaty must translate its general provisions into domestic tobacco control laws and regulations within a certain time frame -- for example, by enacting laws within three years to minimize public exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke, requiring health warning labels on tobacco products, and restricting sales of cigarettes to minors.

Despite this example, most voluntary codes still benefit corporations more than they do civil society. Indeed, it seems that the more harmful the product and the greater industry's wrongdoing, the wider the proliferation of voluntary codes of conduct.

Tobacco company documents lay bare the widespread corporate practice of utilizing voluntary codes to scuttle, control, delay or water down more effective government intervention. But these revelations along with reporting on breaches and violations of codes are making people around the world increasingly skeptical of both voluntary codes, and of the corporations themselves.

"What's the answer?" we asked Patti Lynn. "More international binding regulations. The Global Tobacco Treaty is a good model: local control with international backing and support."

Until that becomes a reality, the public would be well-served to better understand the strategic applications of these codes and their effect on policy, and to urge their replacement with independent inspection mechanisms, more binding and effective international regulations, and more effective enforcement schemes.